By Libby Sutherland

In recent times, colleges and universities have embraced the notion that more administrators, more programming, and more initiatives must necessarily be a good thing. However, because of these fancy new “improvements,” tuition has hiked, yet students have not reaped any significant academic benefits despite this ever-increasing cost. As we review the changing nature of academia, we must ask ourselves: is it really worth it?

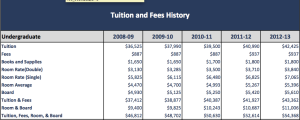

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average admission cost for private four-year institutions has risen by 49% over the last decade. At Washington and Lee, tuition between the years 2000 and 2010 has more than doubled, however. This doubling in tuition has been mirrored by many of our peers as well, reflecting an unsettling trend in higher education today as top universities engage in a never-ending competition to raise their price tags, perhaps in an effort to artificially increase their perceived value.

Certainly there are a number of contributing factors to increasing tuition rates, but perhaps none explain the rise in tuition better than the administrative bloat affecting so many universities today, including W&L.

Bryan Price, the Assistant Provost and Director of Institutional Effectiveness at Washington and Lee, maintains that administration growth is necessary in order to accommodate the number of enrolled students increasing by about 275 – 300 students over the past 20 years. He said that management personnel at W&L has increased by 30% in that same time period. Price also cited technological changes, necessary increase of human resource management, and external mandates as other reasons for administration growth.

According to a study conducted by Jay P. Greene at the Goldwater Institute, the number of full-time administrators per 100 students at America’s leading universities grew by 39 percent between 1993 and 2007 while the number of employees engaged in teaching, research or service only grew by 18 percent. Inflation-adjusted spending on administration per student increased by 61 percent during the same period, while instructional spending per student rose 39 percent.

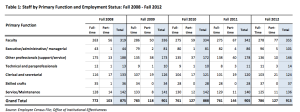

W&L’s institutional research for the academic year of 2011-2012 lists a total number of 267 full time instructional staff members compared to 278 administrative staff members. Price said that the records for 2013-14 show numbers of 253 full time instructional faculty and “a total of 40 individuals with faculty status, which would include librarians and coaches among several other occupations, that serve in an administrative roles full-time. Although they have faculty status, they are not full-time instructional faculty, and most of them do not act in a supervisory role over other faculty.”

Between the years of 2012 and 2013, the Institutional Effectiveness reports no longer counted University administrators and professionals in the same category, instead dividing into two separate categories: “executive/administrative/managerial” and “other professionals (support/service).” Even after this distinction, the report for Fall 2012 shows a number of 101 employees in executive/administrative/managerial positions. According to Price, the student to professor ratio is 8:1 and the student to administration ratio is 21:1, but it is unclear whether the latter ratio is representative of the much higher number of administrative faculty listed on the institutional research reports or the lower number that Price provided.

The greater implications of bureaucratic inflation include a shift of resources and attention away from teaching towards a body of administrators who “do little to advance the central mission of universities,” according to Benjamin Ginsberg, a professor of Political Science at Johns Hopkins University. Essentially, the imbalance in administrative growth compared to professor growth means more staff-induced programs and not enough professors to accommodate students.

Students spend multiple days of a given week in classes with their professors and are much more likely to have a closer relationship with them than administrators. Yet at most schools, professors have little say in decisions regarding issues such as tuition, admission policies, and the size of the student body.

Yearly tuition increases are to be expected but when these increases are several times the rate of inflation there should be a call for change. According to Bain & Company’s The Sustainable University, “Many institutions have operated on the assumption that the more they build, spend, diversify and expand, the more they will persist and prosper. But instead, the opposite has happened: Institutions have become overleveraged.”

When new administrative programs are created, old similar programs are often still left running resulting in confusion and complexity that makes efficiency difficult. Additionally, many school administrations include an unnecessary hierarchy, the staple of all good bureaucracies—too many middlemen tasked with too few essential responsibilities.

Aside from the financial standpoint, the imbalanced proportion of professor growth rate to administrative growth rate could impair students’ experiences. Our University’s most recent change involves an expensive third year housing plan while other issues such as the students’ wavering ability to register for their first choice classes go overlooked. The administration works to shape the vision and organization of the University but administrative bloat can harm their efficiency. Though change and improvement of Student Affairs is important, academics should be at the heart of our values. We should think carefully about what it means to forgo hiring another professor for the sake of adding to an already large administration.